Lately, and by mere coincidence, I was discussing programming language choices. When or why should you choose language X over Y. And apart from the usual suspects like

- “familiarity in the team”

- “interoperability with other pieces in the ecosystem” and

- “existing dependencies that we can leverage”

the idea of how to deal with complexity came up.

In this blog post I would like to explore an idea that I can so clearly see with graphs in my mind, but takes more than a quick chat to get across. So hopefully, next time I’m in a position to talk about languages or any other technology to tackle a problem, I can point to random graphs1 in this article and it will make more sense to my interlocutor.

The graphs here were made with jazcarate :: Rough Graph.

Limits

So, let’s start by setting the groundwork for the next graphs. Some axioms we’ll assume true for the sake of discussion:

Complexity

There is an upper- and lower-bound on the complexity of any given system.

The lower limit should be fairly easy to convince, there is such thing as a trivial program2. On the other hand, the higher bound. And this is a bit more contentious. One can think of this limit as either:

- The allowed limit of the universe. A sub-system can never be more complex than the system on which it is embedded.

- Or, if simulation theory is too scary, the maximum capacity of the given team to tackle.

Either way, complexity is be bounded for the sake of this thought experiment.

Costs

There are many ways to measure costs. In this post, let’s not dwell much on what unit of measurement we chose. In other words, pick whichever is more relatable to you, and I think that my explorations would still make sense:

- Lines of code

- Number of entities in the ER model.

- Human Hours

- Money spent

- Number of sticky notes in the “😟” column in the retrospective.

- other

But any of these will be, as complexity, bounded at both ends. These two parameters give us a neat 2-dimensional space to explore the cost/complexity of things. So, without further ado, I present you with the first graph.

Types

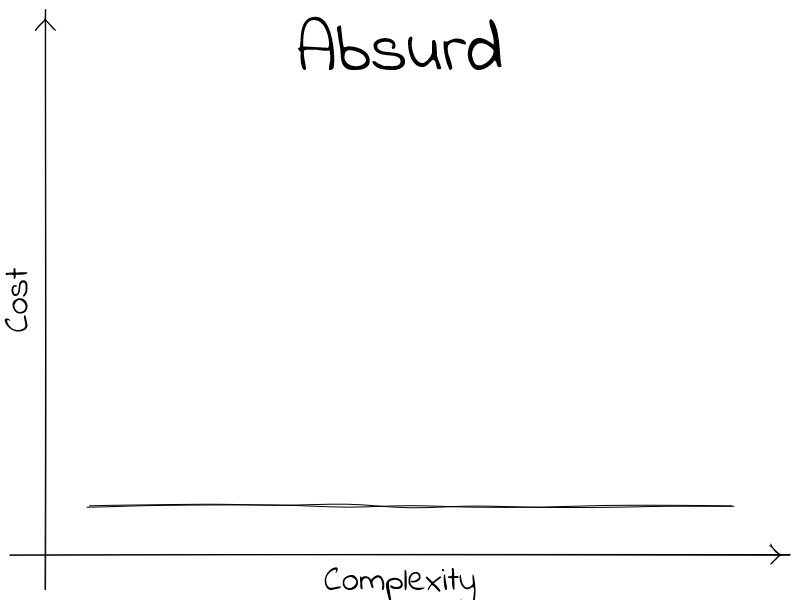

Absurd scenario

No matter the complexity, the cost is constant.

With much grievances; I’ll tell you that there exists no technology that can deliver on this. Complexity will always carry with it a cost. There might be technologies that promise this kind of behavior. They don’t exist3.

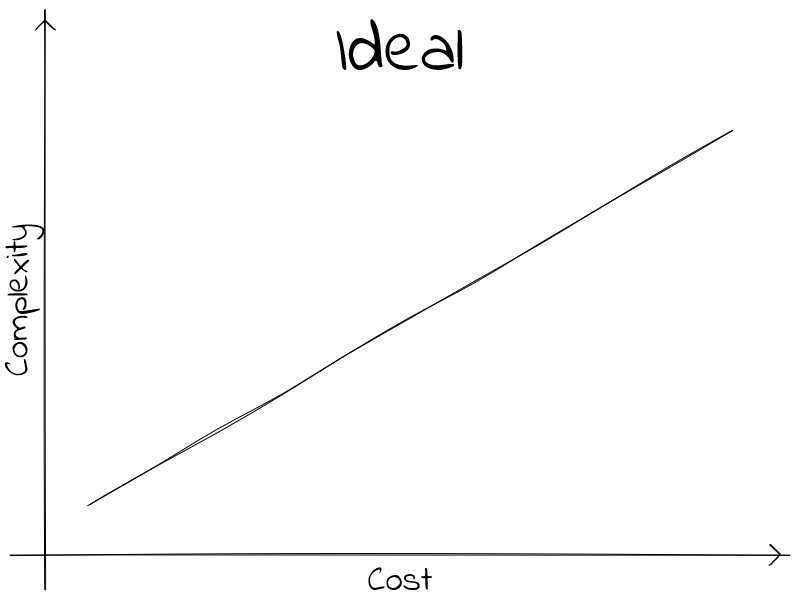

Ideal scenario

So a better notion is that there is a lower bound of how much complexity incurs in cost. I think it would not be unreasonable to propose that the marginal cost is proportional to the change of complexity.

With this mindset, we can establish a “minimum” graph. Technologies might promise better ratios, but we should mistrust.

It is worth mentioning that in all these graphs, a given complexity in the horizontal axis is but the accumulation of costs to reach to that complexity level, as to reach a complexity level of \(n\), one must first cover \(n-\epsilon\) (where \(\epsilon \in \mathbb{R}_{>0}\)). If we call \(f\) the function that we are plotting, then there exists a \(\Delta f \colon \mathbb{Complexity} \mapsto \mathbb{Cost}\) where \(f(complexity) = \int_{0}^{complexity} \Delta f(x) \,dx\). A useful corollary from this fact, is that our graphs are monotonically non-decreasing. And those are fun! 😺.

Now that we established a common ground to talk about complexity and cost, let’s dive into three distinct categories of technologies: Pay as you go, Debt and, Upfront.

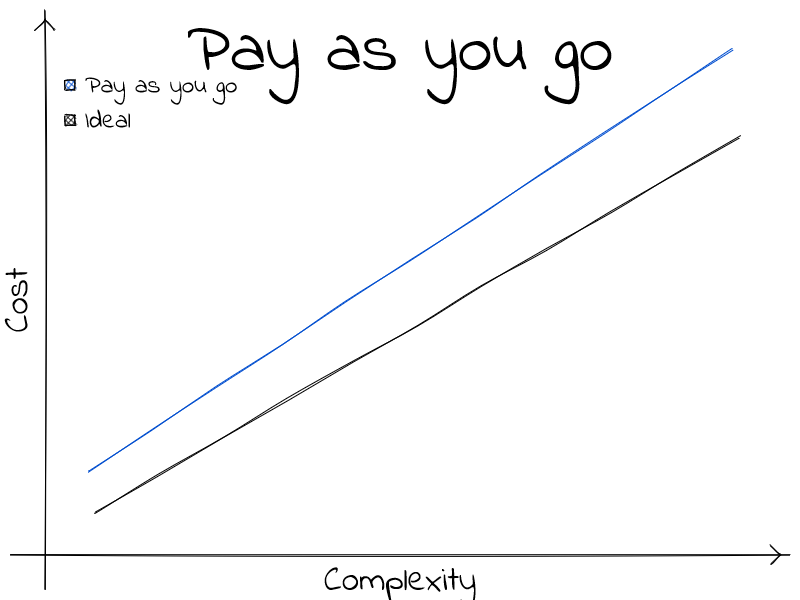

Pay as you go

Maybe the most alluring. The more complex a problem, the more it costs to solve. It is a sensible way of understanding technology. The many flavors of pay as you go differ from one another by their slope, or their initial cost. c-like languages fall squarely here.

Technologies here could be plotted with a slightly different slope or initial height. I don’t much care about the details comparing each of these technologies 😅. They are great all-around options. Jack of all trades, master of none. I see these technologies as the backbone of the software industry. Some have a steeper \(\Delta f\), where some have a costlier start; but on in all, they grow linearly. Never being able to have a slope less than the ideal scenario.

Examples of these are:

- Java

- c

- SQL

- Hibernate*

All of these follow the pattern:

Simple things are cheap. Complex things are costly.

A note on Hibernate, and many others: Complexity is treated here as a one-size-fits-all kind of thing. The reality, sadly, is much more complicated. If you were to focus on the \(\frac{cost}{complexity}\) of say, switching databases. Then an ORM like Hibernate makes a upfront cost for simple things to have a better marginal cost when reaching the complex side of the spectrum.

But we are not here to talk about workhorses, but rather the odd ones out. So on to the more interesting ones!

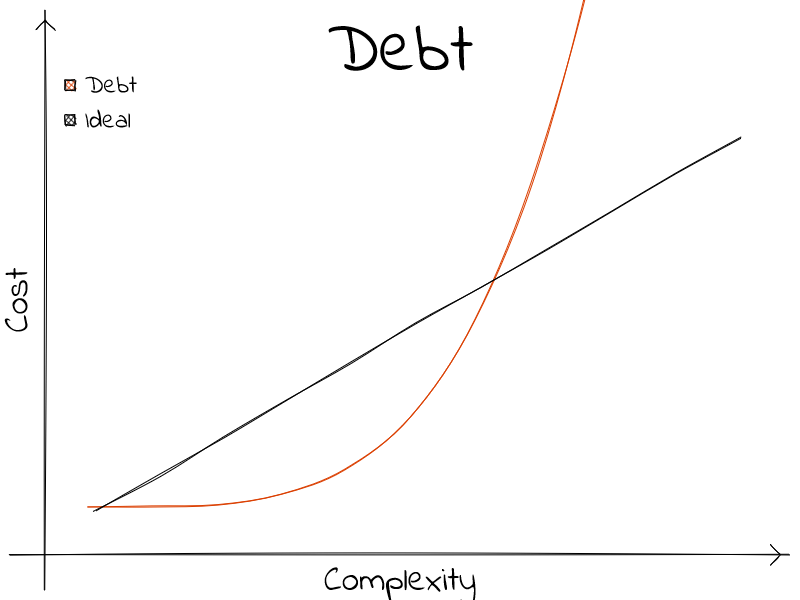

Debt

These are the most interesting to me. Technologies that promise you a very low barrier of entry.

Simple things can be done incredibly fast and easy, without hindering other non-functional aspects like security or speed. But, as in real life, these are not free. At some point in the complexity scale, things start to become hard. And way hard at that.

All those nice defaults start to work against your custom needs. You start to fight the framework, find ways around checks and validations. Ways that deviate from the secure, fast, reliable path.

Examples of these are:

- Node’s ecosystem

- Ruby on Rails

- no-code

And Ruby on Rails or Node.js fans might argue that that is not the case; that the cost does rarely increase. And that this reflects on my general lack of understanding of the deeper systems, or the metaprogramming machinery, or yet another dependency that can be used both as an import, a CLI, or a bundler ⸮ . For which I will yield, that this is probably true. And that this is not a counterargument, but rather proof. At a certain point, the complexity of a problem intertwines with the complexity of the technology; compounding on the costs.

Thus, the exponentially of the matter. Remember that, the cost at the end of the complexity axis, must always be greater than the ideal scenario. There is no, and will never be, a piece of technology that can beat the cruel reality that complexity carries costs.

But this is a good thing to learn from these: If you know that the complexity of a problem is capped, then these alternatives are just what you need. If you need a CRUD API, some web views with some forms, a little OAuth without much customization; then I encourage the use of these sort of technologies.

Looking at the graph, there is a point where the ideal and the Debt intersects. If you can be sure that the complexity will always be on the left-hand side; then using any other technology will be ill-advised. But, if the threshold does get crossed, then you are stuck between switching to another type of technology, and re-paying all the costs to get you to this point; or deal with an exorbitant \(\frac{cost}{complexity}\).

Partial payment

Be not mistaken, the cost difference before the Debt curve and the Ideal curve meet was paid by the designers of the technology. And we should be grateful that they allow us to offset a big chunk of our costs to their endeavors.

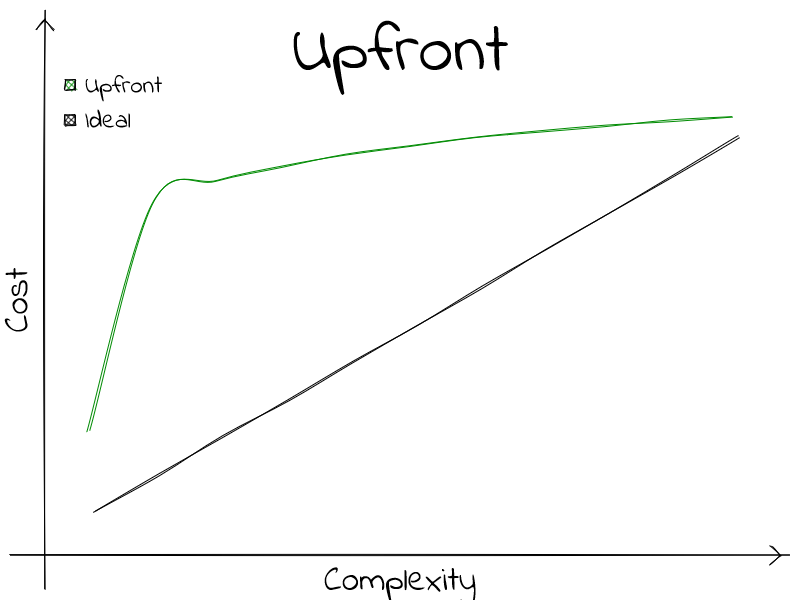

Upfront

Finally: Upfront. These are a treat. You pay a steep cost upfront, but after some turning point, then the marginal cost is cheap. Managing complexities. Composition, ways of meta-programing, having tools for code synthesis are all techniques that pay this cost upfront for future gains.

Some might call this approach over engineering, and it is true; up until the point where failing to have done it, the cost is greater. In other words:

\[overEngineered(complex) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \text{Yes} &: payAsYouGo(complex) \leq upfront(complex) \\ \text{No} &: \text{otherwise.} \\ \end{array} \right.\]Examples of these are:

- Haskell

- Lisp

- Wingman

- Macros

Maybe you are one of the enlightened few to have partially-payed some of the costs and already know about β-reduction, monad composition4, or other techniques to manage complexity; but be not mistaken that that cost will be paid for every other person that has to deal with it in the future.

Conclusion

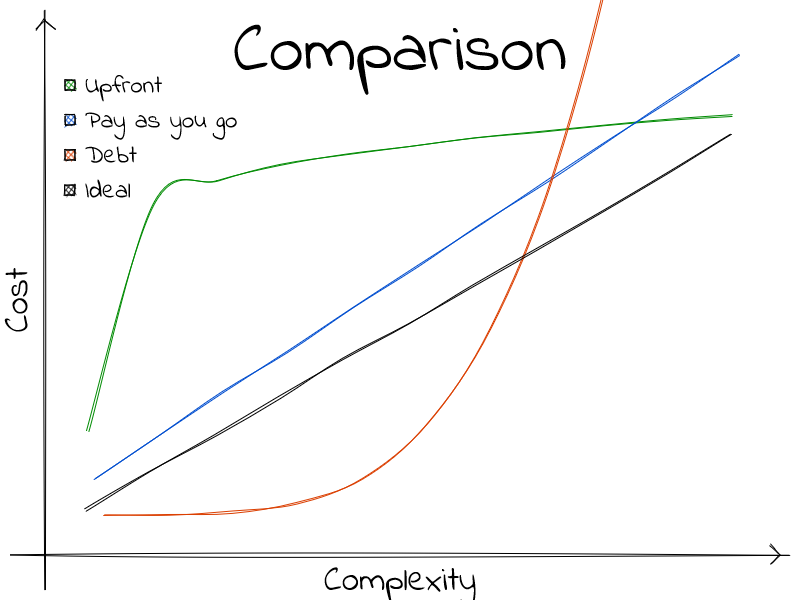

No technology is better or worse in the abstract. It is a choice between good things, and bad things. In this blog post, I wanted to explore a different way of evaluating a piece of technology with just these two axes. And hopefully, give you a new tool to measure up prospects for your next undertaking.

So I leave you with this final question to encapsulate all of these learnings:

Does either cost or complexity have a ceiling in this project?

And then, it is a matter of putting a horizontal or vertical line on the limit and seeing what strategy yields better results.

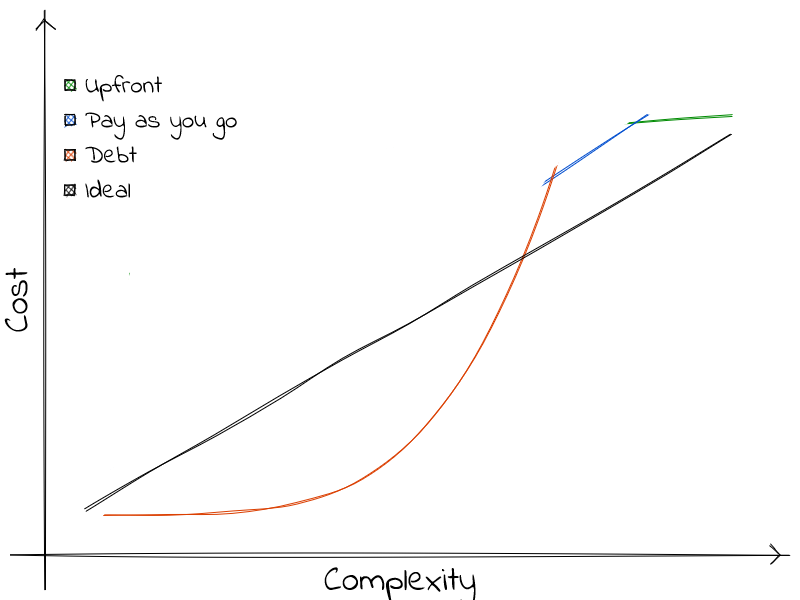

More often than not, one wants to minimize costs but complexity is set. Therefore the 1-picture-summary would be:

\[f(complexity) = min( upfront(complexity), payAsYouGo(complexity), debt(complexity) )\]

I’m not advocating on using a Debt technology at the begging and then switching mid-project; as the cost at the switching point will double; but rather a methodology of choosing the correct shape to deal with the expected complexity of it.

Nobody Gets Fired For Buying IBM

I’ll surrender that choosing a technology is an architectural decision done at the start of a project, and knowing how complex it will end up being is almost impossible. This is why, I think, pay as you go technologies are so prevalent.

-

The idea of a graph with no units, no scale, or raw data to replicate them irks me. If you are like me, think of these not like “graphs”, but rather pretty pictures 😊. ↩

-

If you allow the idea of representing a program as data, and are Haskell inclined, then

pure :: IO ()would be what I refer to as a “trivial complexity”, as it does nothing. It has no explanation on what it does, and there is nothing that can be taken from it to reach a valid program; hence the lower bound on complexity. ↩ -

No free lunch theorem. ↩

-

Or rather lack thereof. ↩